Blog

Beef over beef. On CETA and the history of the European growth hormone ban

In the wake of controversies over the Dutch ratification of the CETA trade deal between Canada and the EU, Koen van Zon asks where concerns over hormone-raised beef originated. This blog goes back to the events leading up to the European Community’s ban on growth hormones in the meat industry in 1985. Koen shows that the debate, which involved a variety of actors across the Community, was fuelled by sentiments which made the question of regulating food safety a highly sensitive affair – and not just within Europe

“Hormones in veal make the French hysterical”, the Dutch daily NRC wrote on 1 October 1980

In what was a close call, the Dutch House of Representatives voted yesterday to ratify CETA (the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement, a trade deal between the European Union and Canada). The Dutch ratification of CETA still hangs in the balance, however, since the senate is undecided as of yet. The political debate on CETA has dominated Dutch news the past few weeks, with concerns being raised over the dispute settlement mechanism, but also to the Canadian standards of food safety. A government coalition party demanded the minister to pledge that Canadian hormone-treated meat would not be sold on the European market.

It is not the first time that controversy arises over hormone-treated meat. It is a powerful symbol, much like chlorinated chicken, at a time when free trade is met with substantial resistance. The origins of this symbol date back to the 1970s, when a scandal led to a European ban on using growth hormones in cattle breeding. Concerns over animal welfare notwithstanding, it was the welfare of European consumers that was central to this debate. The history of the hormone ban puts into perspective what we mean when we speak about high standards in food safety, and shows how national and European policymakers were keen to assuage public outcries over consumer safety.

The scandal

The controversy about hormone raised beef originated at the school of the Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in Milan in 1977, where numerous school children showed signs of a premature onset of puberty. Two years later, an article in the medical journal The Lancet, investigating the case, suggested that the hormone oestrogen was the culprit, which had probably been served to the children through meat in the school cafeteria. For farmers, growth hormones were a way to promote growth and muscle build-up in animals, and to bring down the production costs of meat. Although some individual European states regulated against this practice, an Italian consumer organisation reported in 1980 that it had discovered 30,000 jars of baby food from France, containing veal with forbidden hormones in it.

“The question of growth hormones was now no longer a question of scientific evidence, but of trade interests”

What followed was a Europe-wide suspicion and scrutiny of the use of growth hormones in cattle breeding. Consumer organisations across the European Community (EC) raised doubts as to the safety of hormone-raised beef. The French consumer organisation even mobilised the readers of its magazine Que choisir for a so-called buycott, which caused the consumption of veal in France to plummet with 70 percent and veal prices to drop. On the European common market for agricultural produce, such a decline hit hard not just in France, but across the Community.

The EC responds

With European consumers in an uproar, pressure mounted on the European Community to take a stand in the debate on growth hormones. On one side, the meat industry lobbied against regulation, even arguing that prohibition of alcohol in the United States had led to a black market and bootlegging, and that the same could happen for hormone-raised beef. On the other side was the European consumer organisation BEUC, with the French consumer organisation as its most vocal member organisation. Backed by alarmist media reporting, BEUC campaigned for a ban on growth hormones. BEUC found a willing ear in Strasbourg, where the European Parliament had been directly elected for the first time in 1979, and saw the issue of consumer protection as a field to show its responsiveness to public concerns. BEUC and the European Parliament argued not just for higher standards of food safety, but also that the use of growth hormones was excessive considering that European farmers overproduced on a massive scale as a result of the European Common Agricultural Policy. In addition to the infamous butter mountains and milk lakes, there were 400,000 tons of beef in European storage houses.

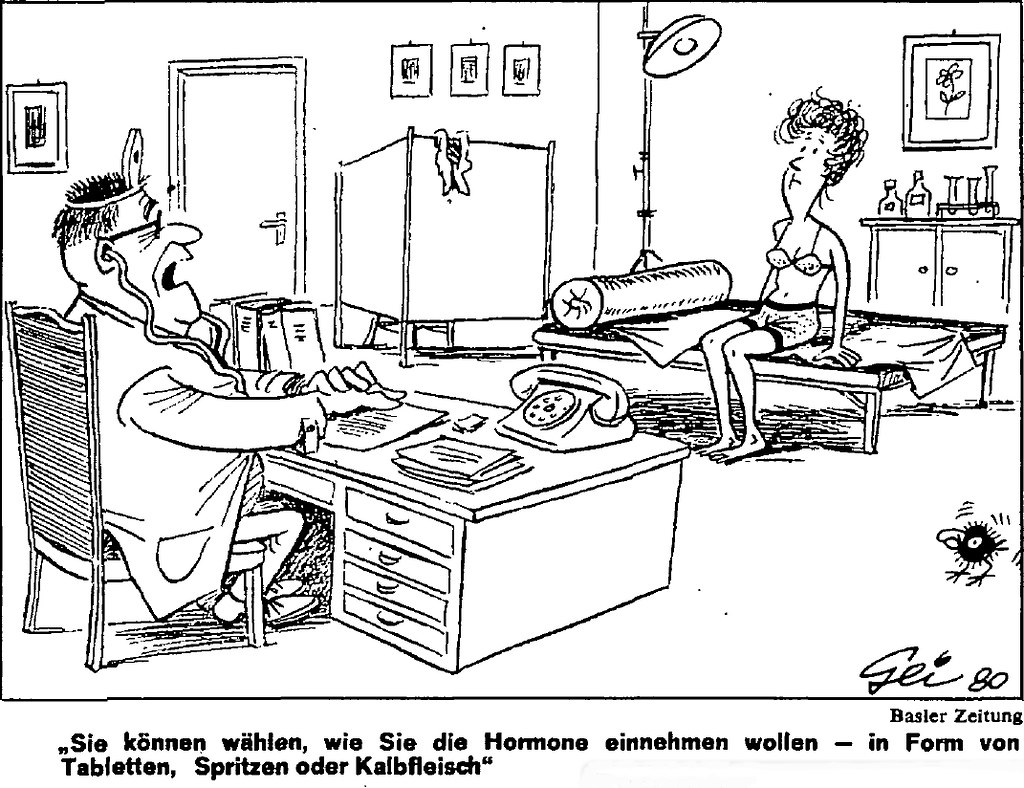

A cartoon in Der Spiegel from November 1980, where the doctor offers his patient the option to ingest the prescribed hormones through tablets, injections, or veal.

The European Commission responded as it often did: by initiating a scientific investigation. Sixty of the most distinguished veterinary and food scientists in Europe came together in a working group which concluded, one hormone after another, that there were no demonstrable dangers to consumer health, given appropriate production circumstances. The scientific evidence came slowly, however, and by the mid-1980s, many member states had banned growth hormones, unwilling to await Community action. The question of growth hormones was now no longer a question of scientific evidence, but of trade interests. National bans erected trade barriers on the Community’s internal agricultural market, and so it made more sense to harmonise the strict rules member states had imposed rather than persuading member states to back down. In 1985, the Community issued a ban on five growth hormones.

Trade conflicts

The ban sparked outrage among some of the Community’s trading partners. Most affected was the US, where beef exports to the Community fell by 95 percent within five years. A trade conflict ensued, which resulted in a deal where the EC and the US would jointly certify that US beef exports were hormone-free. Canada also objected to the ban, but contrary to the US, its beef exports to the Community amounted to less than 0.02 percent.

“Fears that the European market will be flooded by Canadian hormone-raised beef are largely unfounded”

Almost forty years on, the issue of hormone-raised beef still sparks controversy. Concerns over animal welfare and the legal consequences of CETA notwithstanding, fears that the European market will be flooded by Canadian hormone-raised beef are largely unfounded. After all, Canadian meat imports are subjected to veterinary checks at the European border and that Canadian meat exports to the EU are marginal to begin with.

Lessons learned?

The current controversy over CETA does reveal a number of other striking dynamics. First of all, it appears that maintaining high standards of product safety in international trade is generally regarded as a good thing – whether there is scientific evidence in support of these standards or not. Paradoxically, then, the regulator enforcing these high standards, the EU, is often portrayed as a meddlesome bureaucracy that is out of touch with citizens.

Second, the political dynamic that came with the European hormone ban shows that consumer protection, however it may be framed, is a very delicate issue in European governance. In response to public outcries about food safety, the European Commission’s customary approach of installing a scientific committee fell short of assuaging public sentiments. Member states fell caved in one after another. The narrative of the vulnerable consumer was so dominant in this debate that even meat producers, who opposed the hormone ban, tapped into this image by conjuring up the image of bootleggers flogging contraband beef on the black market. The most effective coalition in this debate, therefore, consisted of European consumer organisations, backed by the European Parliament and alarmist media reporting.

As the EU-27 and Great Britain gear up to negotiate a trade deal before the end of 2020, there is every chance that controversies similar to the one on growth hormones will surface. The question is what impact these will have on the negotiations, and which new coalitions will form this time around.