Blog

Fighting for food: European consumers and the Common Agricultural Policy

The largest farmers’ demonstration in postwar European history, in protest against reform of the Common Agricultural Policy, turns 5o today. Alessandra Schimmel argues in this blog that it prompts us to consider other groups’ criticism of this policy as well. Since the early 1970s, European consumer groups have repeatedly raised their concerns about the Common Agricultural Policy, addressing its failure to consider the consumer interest.

1971 demonstration in Brussels against the Mansholt Plan

Fifty years ago today, on 23 March 1971, around 100.000 European farmers took to the streets of Brussels, in protest against the Mansholt Plan. The plan, devised by European Commissioner for Agriculture Sicco Mansholt, was intended to reshape the European Economic Community’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) by increasing productivity and self-sufficiency among European farmers. In practice, the reforms demanded the halving of the agricultural labour force, and major cuts of the amount of land used for farming. Farmers saw their livelihoods threatened, and backed by national and European farmers’ organisations, joined together in the largest protest in Belgian history. From all over Western Europe, farmers made their way to Brussels, where they marched through the streets with signs, banners, and pitchforks. Ever since, farmers have held prominence in criticism of Europe’s agricultural policy, but they were by no means the only group with a stake in the CAP. Since the early 1970s, European consumer groups have consistently criticised the policy, extending into today’s discussions about the European Commission’s Farm to Fork strategy.

“The main problem was that the Common Agricultural Policy had been designed as a policy for the benefit of farmers, not of consumers”

The consumer point of view

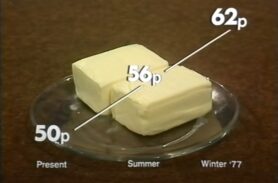

In 1977, the British program ‘Money go round‘ raised the issue of EEC food prices

The scale and complexity of the Common Agricultural Policy meant that various interests and viewpoints had to be integrated in addition to those of farmers, but they were often overlooked. European consumer groups, since the early 1960s organised in the umbrella consumer group BEUC (Bureau Européen des Unions de Consommateurs, ‘European Bureau of Consumers’ Unions’), were increasingly raising their concerns about the CAP. To them, the consumer interest was not taken into account – a major problem, since food was, and still is, regarded as the most essential of the consumer’s needs.

The main problem, European consumer groups argued, was the fact that the Common Agricultural Policy had been designed as a policy for the benefit of farmers, not of consumers. Its principles were to guarantee farmers’ incomes by way of fixed minimum prices, to stimulate productivity, and to stabilise the market through price policy. And although one of the CAP’s aims was to ensure reasonable food prices for consumers, European consumer representatives felt that the consumer interest was insufficiently addressed in the field of food and agriculture.

“Consumers felt they were directly paying for farmers’ subsidies through the high food prices, which was a constant source of conflict.”

Criticising the Common Agricultural Policy

One of the EEC’s infamous butter mountains

BEUC’s concrete criticisms of the Common Agricultural Policy were threefold. First, food prices were consistently too high, in order to ensure the farmers’ incomes. Consumers felt they were directly paying for farmers’ subsidies through the high food prices, which was a constant source of conflict. For less affluent consumers in particular, who spent a relatively larger share of their income on food, this was especially problematic. Secondly, the system of standard prices and market guarantees led to structural surpluses: the infamous butter mountains and milk lakes. The surpluses then were dumped on the world market against minimum prices, whereas the European consumer always paid the full price. When the European Commission, in the late 1970s, devised a scheme to cheaply sell butter to the Soviet Union, in the midst of the Cold War, this proved a highly controversial move, and led consumer organisations to claim that the Commission was not acting in the European consumers’ interest. Thirdly, the Common Agricultural Policy was merely focused on the production side, and unconcerned with issues relating to the quality, transport, packaging, and environmental effects of food – aspects that were becoming more and more important to consumers.

Towards a European food policy

The European consumer groups nevertheless acknowledged the importance of the CAP, with its guaranteed food supplies, to the European Economic Community and the process of European integration in general. However, in order to represent all interests concerned, BEUC argued that the agricultural policy needed to transform from a sectoral agricultural policy (which mostly benefited farmers) into a genuine food policy, in which the interests of farmers, consumers, the environment, and others concerns were addressed. In order achieve this, consumer representatives sought to influence the Community’s agricultural ministers, the European Parliament, and set up actions in the member states.

The European Commission’s current plans for the Farm to Fork strategy, a cornerstone of the European Green Deal, echoes consumer groups’ demands for a comprehensive food system instead of an agricultural policy, to create a fair and environmentally friendly food system, for everyone involved.